Julia Ward Howe.

FROM SUNSET RIDGE: Poems Old and New. 12mo, $1.50.

REMINISCENCES. With many Portraits and other Illustrations. Crown 8vo, $2.50.

IS POLITE SOCIETY POLITE? and other Essays. With a Portrait of Mrs. Howe. Square 8vo, $1.50.

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO.

Boston and New York.

REMINISCENCES

1819-1899

BY

JULIA WARD HOWE

WITH PORTRAITS AND OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1899

COPYRIGHT, 1899, BY JULIA WARD HOWE

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

CHAPTER XIII

THE BOSTON RADICAL CLUB: DR. F. H. HEDGE

Mr. Emerson had a brief connection with the Radical Club; and this may be a suitable place in which to give my personal impressions of the Prophet of New England. In remembering Mr. Emerson, we should analyze his works sufficiently to be able to distinguish the things in which he really was a leader and a teacher from other traits peculiar to himself, and interesting as elements of his historic character, but not as features of the ideal which we are to follow. Mr. Emerson objected strongly to newspaper reports of the sittings of the Radical Club. The reports sent to the New York “Tribune” by Mrs. Louise Chandler Moulton were eagerly sought and read in very distant parts of the country. I rejoiced in this. It seemed to me that the uses of the club were thus greatly multiplied and extended. It became an agency in the great church universal. Mr. Emerson’s principal objection to the reports was that they interfered with the freedom of the occasion. When this objection failed to prevail, he withdrew from the club almost entirely, and was never more heard among its speakers.

I remember hearing Mr. Emerson, in his discourse on Henry Thoreau, relate that the latter had once determined to manufacture the best lead pencil that could possibly be made. Having attained this end, parties interested at once besought him to make this excellent article attainable in trade. He said, “Why should I do this? I have shown that I am able to produce the best pencil that can be made. This was all that I cared to do.” The selfishness and egotism of this point of view did not appear to have entered into Mr. Emerson’s thoughts. Upon this principle, which of the great discoverers or inventors would have become a benefactor to the human race? Theodore Parker once said to me, “I do not consider Emerson a philosopher, but a poet lacking the accomplishment of rhyme.” This may not be altogether true, but it is worth remembering. There is something of the vates in Mr. Emerson. The deep intuitions, the original and startling combinations, the sometimes whimsical beauty of his illustrations,—all these belong rather to the domain of poetry than to that of philosophy. The high level of thought upon which he lived and moved and the wonderful harmony of his sympathies are his great lesson to the world at large. Despite his rather defective sense of rhythm, his poems are divine snatches of melody. I think that, in the popular affection, they may outlast his prose.

I was once surprised, in hearing Mr. Emerson talk, to find how extensively read he was in what we may term secondary literature. Although a graduate of Harvard, his reading of foreign literatures, ancient and modern, was mostly in translations. I should say that his intellectual pasture ground had been largely within the domain of belles-lettres proper.

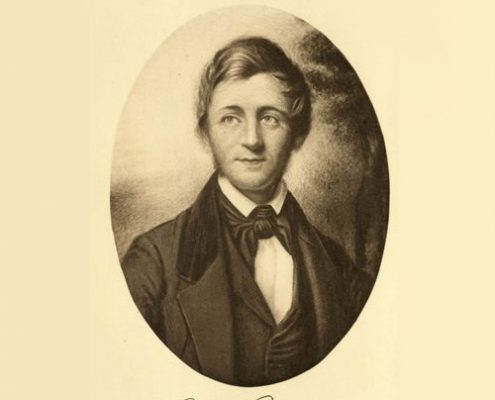

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

From a photograph by Black.

He was a man of angelic nature, pure, exquisite, just, refined, and human. All concede him the highest place in our literary heaven. First class in genius and in character, he was able to discern the face of the times. To him was entrusted not only the silver trump of prophecy, but also that sharp and two-edged sword of the Spirit with which the legendary archangel Michael overcomes the brute Satan. In the great victory of his day, the triumph of freedom over slavery, he has a record not to be outdone and never to be forgotten.

CHAPTER XIV

MEN AND MOVEMENTS IN THE SIXTIES

This dear man was a great addition to the thought-power current in Boston society. He had lived much abroad, and was for many years a student of Swedenborg and of Fourier. His cast of mind was more metaphysical than logical, and he delighted in paradox. In his writings he would sometimes overstate greatly, in order to be sure of impressing his meaning upon his readers or hearers. Himself a devout Christian, he nevertheless once said, speaking on Sunday in the Church of the Disciples, that the moral law and the Christian Church were the meanest of inventions. He intended by this phrase to express his sense of the exalted moral and religious obligation of the human mind, the dignity of which ought to transcend the prescriptions of the Decalogue and the discipline of the church. My eldest daughter, then a girl of sixteen, said to me as we left the church, “Mamma, I should think that Mr. James would wish the little Jameses not to wash their faces for fear it should make them suppose that they were clean.” Mr. Emerson, to whom I repeated this remark, laughed quite heartily at it. In anecdote Mr. James was inexhaustible. His temperament was very mercurial, almost explosive. I remember a delightful lecture of his on Carlyle. I recall, too, a rather metaphysical discourse which he read in John Dwight’s parlors, to a select audience. When we went below stairs to put on our wraps, I asked a witty friend whether she had enjoyed the lecture. She replied that she had, but added, “I would give anything at this moment for a look at a good fat idiot,” which seemed to show that the tension of mind produced by the lecture had not been without pain.

CHAPTER XX

FRIENDS AND WORTHIES: SOCIAL SUCCESSES

Time would fail me if I should undertake to mention the valued friendships which have gladdened my many years in Boston, or to indicate the social pleasures which have alternated with my more serious pursuits. One or two of these friends I must mention, lest my reminiscences should be found lacking in the good savor of gratitude.

I have already spoken of seeing the elder Richard H. Dana from time to time during the years of my young ladyhood in New York. He himself was surely a transcendental, of an apart and individual school. Nevertheless, the transcendentals of Boston did not come within either his literary or his social sympathies. I never heard him express any admiration for Mr. Emerson. He may, indeed, have done so at a later period; for Mr. Emerson in the end won for himself the heart of New England, which had long revolted at his novelties of thought and expression. Mr. Dana’s ideal evidently was Washington Allston, for whom his attachment amounted almost to worship. The pair were sometimes spoken of in that day as “two old-world men who sat by the fire together, and upheld each other in aversion to the then prevailing state of things.”

From a photograph lent by Mrs. John Murray Forbe

Tom Appleton, as he was usually called, was certainly a man of parts and of great reputation as a wit, but I should rather have termed him a humorist. He cultivated a Byronic distaste for the Puritanic ways of New England. In truth, he was always ready for an encounter of arms (figuratively speaking) with institutions and with individuals, while yet in heart he was most human and humane. Born in affluence, he did not embrace either business or profession, but devoted much time to the study of painting, for which he had more taste than talent. It was as a word artist that he was remarkable; and his graphic felicities of expression led Mr. Emerson to quote him as “the first conversationalist in America,” an eminence which I, for my part, should have been more inclined to accord to Dr. Holmes.

CHAPTER VII

MARRIAGE: TOUR IN EUROPE

Mr. Emerson somewhere speaks of the romance of some special philanthropy. Dr. Howe’s life became an embodiment of this romance. Like all inspired men, he brought into the enterprises of his day new ideas and a new spirit. Deep in his heart lay a sense of the dignity and ability of human nature, which forced him to reject the pauperizing methods then employed in regard to various classes of unfortunates. The blind must not only be fed and housed and cared for; they must learn to make their lives useful to the community; they must be taught and trained to earn their own support. Years of patient effort enabled him to accomplish this; and the present condition of the blind in American communities attests the general acceptance of their claim to the benefits of education and the dignity of useful labor.

…………………………………………….

I saw Grisi in the great rôle of Semiramide, and with her Brambilla, a famous contralto, and Fornasari, a basso whom I had longed to hear in the operas given in New York. I also saw Mlle. Persiani in “Linda di Chamounix” and “Lucia di Lammermoor.” All of these occasions gave me unmitigated delight, but the crowning ecstasy of all I found in the ballet. Fanny Elssler and Cerito were both upon the stage. The former had lost a little of her prestige, but Cerito, an Italian, was then in her first bloom and wonderfully graceful. Of her performance my sister said to me, “It seems to make us better to see anything so beautiful.” This remark recalls the oft-quoted dialogue between Margaret Fuller and Emerson apropos of Fanny Elssler’s dancing:—

“Margaret, this is poetry.”

“Waldo, this is religion.”

…………………………………………….

We made some stay in Paris, of which city I have chronicled elsewhere my first impressions. Among these was the pain of hearing a lecture from Philarète Chasles, in which he spoke most disparagingly of American literature, and of our country in general. He said that we had contributed nothing of value to the world of letters. Yet we had already given it the writings of Irving, Hawthorne, Emerson, Longfellow, Bryant, and Poe. It is true that these authors were little, if at all, known in France at that time; but the speaker, proposing to instruct the public, ought to have informed himself concerning that whereof he assumed to speak with knowledge.

CHAPTER VIII

FIRST YEARS IN BOSTON

In the autumn of 1844 we returned from our wedding journey, and took up our abode in the near neighborhood of the city of Boston, of which at intervals I had already enjoyed some glimpses. These had shown me Margaret Fuller, holding high communion with her friends in her well-remembered conversations; Ralph Waldo Emerson, who was then breaking ground in the field of his subsequent great reputation; and many another who has since been widely heard of. I count it as one of my privileges to have listened to a single sermon from Dr. Channing, with whom I had some personal acquaintance. I can remember only a few passages. Its theme must have been the divine love; for Dr. Channing said that God loved black men as well as white men, poor men as well as rich men, and bad men as well as good men. This doctrine was quite new to me, but I received it gladly.

The time was one in which the Boston community, small as it then was, exhibited great differences of opinion, especially regarding the new transcendentalism and the anti-slavery agitation, which were both held much in question by the public at large. While George Ripley, moved by a fresh interpretation of religious duty, was endeavoring to institute a phalanstery at Brook Farm, the caricatures of Christopher Cranch gave great amusement to those who were privileged to see them. One of these represented Margaret Fuller driving a winged team attached to a chariot on which was inscribed the name of her new periodical, “The Dial,” while the Rev. Andrews Norton regarded her with holy horror. Another illustrated a passage from Mr. Emerson’s essay on Nature—”I play upon myself. I am my own music”—by depicting an individual with a nose of preternatural length, pierced with holes like a flageolet, upon which his fingers sought the intervals. Yet Mr. Cranch belonged by taste and persuasion among the transcendentalists.

As my earliest relations in Boston were with its recognized society, I naturally gave some heed to the views therein held regarding the transcendental people. What I liked least in these last, when I met them, was a sort of jargon which characterized their speech. I had been taught to speak plain and careful English, and though always a student of foreign languages, I had never thought fit to mix their idioms with those of my native tongue. Apropos of this, I remember that the poet Fitz-Greene Halleck once said to me of Margaret Fuller, “That young lady does not speak the same language that I do,—I cannot understand her.” Mr. Emerson’s English was as new to me as that of any of his contemporaries; but in his case I soon felt that the thought was as novel as the language, and that both marked an epoch in literary history. The grandiloquence which was common at that time now appears to me to have been the natural expression of an exhilaration of mind which carried the speaker or writer beyond the bounds of commonplace speech. The intellect of the time had outgrown the limits of Puritan belief. The narrow literalism, the material and positive view of matters highly spiritual, abstract, and indeterminate, which had been handed down from previous generations, had become irreligious to the foremost minds of that day. They had no choice but to enter the arena as champions of the new interpretation of life which the cause of truth imperatively demanded.

I speak now of the transcendental movement as I had opportunity to observe it in Boston. Let us not ignore the fact that it was a world movement. The name seems to have been borrowed from the German phraseology, in which the philosophy of Kant was termed “the transcendental philosophy.” More than this, the breath which kindled among us this new flame of hope and aspiration came from the same source. For this was the period of Germany’s true glory. Her intellectual radiance outshone and outlived the military meteor which for a brief moment obscured all else to human vision. The great vitality of the German nation, the indefatigable research of its learned men, its wholesome balance of sense and spirit, all made themselves widely felt, and infused fresh blood into veins impoverished by ascetic views of life. Its philosophers were apostles of freedom, its poets sang the joy of living, not the bitterness of sin and death.

These good things were brought to us piecemeal, by translations, by disciples. Dr. Hedge published an English rendering of some of the masterpieces of German prose. Longfellow gave us lovely versions of many poets. John S. Dwight produced his ever precious volume of translations of the minor poems of Goethe and Schiller. Margaret Fuller translated Eckermann’s “Conversations with Goethe.” Carlyle wrote his wonderful essays, inspired by the new thought, and adding to it daring novelty of his own. The whole is matter of history now, quite beyond the domain of personal reminiscence.

…………………………………………….

I first heard of Theodore Parker as the author of the sermon on “The Transient and the Permanent in Christianity.” At the time of its publication I was still within the fold of the Episcopal Church, and, judging by hearsay, was prepared to find the discourse a tissue of impious and sacrilegious statements. Yet I ventured to peruse a copy of it which fell into my hands. I was surprised to find it reverent and appreciative in spirit, although somewhat startling in its conclusions. At that time the remembrance of Mr. Emerson’s Phi Beta address was fresh in my mind. This discourse of Parker’s was a second glimpse of a system of thought very different from that in which I had been reared.

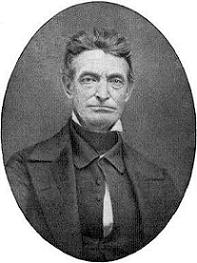

Some time in the fifties, my husband spoke to me of a very remarkable man, of whom, he said, I should be sure to hear sooner or later. This man, Dr. Howe said, seemed to intend to devote his life to the redemption of the colored race from slavery, even as Christ had willingly offered his life for the salvation of mankind. It was enjoined upon me that I should not mention to any one this confidential communication; and to make sure that I should not, I allowed the whole matter to pass out of my thoughts. It may have been a year or more later that Dr. Howe said to me: “Do you remember that man of whom I spoke to you,—the one who wished to be a saviour for the negro race?” I replied in the affirmative. “That man,” said the doctor, “will call here this afternoon. You will receive him. His name is John Brown. Thus admonished, I watched for the visitor, and prepared to admit him myself when he should ring at the door.

From a photograph about 1857.

This took place at our house in South Boston, where it was not at all infra dig. for me to open my own door. At the expected time I heard the bell ring, and, on answering it, beheld a middle-aged, middle-sized man, with hair and beard of amber color, streaked with gray. He looked a Puritan of the Puritans, forceful, concentrated, and self-contained. We had a brief interview, of which I only remember my great gratification at meeting one of whom I had heard so good an account. I saw him once again at Dr. Howe’s office, and then heard no more of him for some time.

I cannot tell how long after this it was that I took up the “Transcript” one evening, and read of an attack made by a small body of men on the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. Dr. Howe presently came in, and I told him what I had just read. “Brown has got to work,” he said. I had already arrived at the same conclusion. The rest of the story is matter of history: the failure of the slaves to support the movement initiated for their emancipation, the brief contest, the inevitable defeat and surrender, the death of the rash, brave man upon the scaffold. All this is known, and need not be repeated here. In speaking of it, my husband assured me that John Brown’s plan had not been so impossible of realization as it appeared to have been after its failure. Brown had been led to hope that, upon a certain signal, the slaves from many plantations would come to him in such numbers that he and they would become masters of the situation with little or no bloodshed. Neither he nor those who were concerned with him had it at all in mind to stir up the slaves to acts of cruelty and revenge. The plan was simply to combine them in large numbers, and in a position so strong that the question of their freedom would be decided then and there, possibly without even a battle.

I confess that the whole scheme appeared to me wild and chimerical. Of its details I knew nothing, and have never learned more. None of us could exactly approve an act so revolutionary in its character, yet the great-hearted attempt enlisted our sympathies very strongly. The weeks of John Brown’s imprisonment were very sad ones, and the day of his death was one of general mourning in New England. Even there, however, people were not all of the same mind. I heard a friend say that John Brown was a pig-headed old fool. In the Church of the Disciples, on the other hand, a special service was held on the day of the execution, and the pastor took for his text the saying of Christ, “It is enough for the disciple that he be as his master.” Victor Hugo had already said that the death of John Brown would thenceforth hallow the scaffold, even as the death of Christ had hallowed the cross.

The record of John Brown’s life has been fully written, and by a friendly hand. I will only mention here that he had much to do with the successful contest which kept slavery out of the territory of Kansas. He was a leading chief in the border warfare which swept back the pro-slavery immigration attempted by some of the wild spirits of Missouri. In this struggle, he one day saw two of his own sons shot by the Border Ruffians (as the Missourians of the border were then called), without trial or mercy. Some people thought that this dreadful sight had maddened his brain, as well it might.

I recall one humorous anecdote about him, related to me by my husband. On one occasion, during the border war, he had taken several prisoners, and among them a certain judge. Brown was always a man of prayer. On this occasion, feeling quite uncertain as to whether he ought to spare the lives of the prisoners, he retired into a thicket near at hand, and besought the Lord long and fervently to inspire him with the right determination. The judge, overhearing this petition, was so much amused at it that, in spite of the gravity of his own position, he laughed aloud. “Judge ——,” cried John Brown, “if you mock at my prayers, I shall know what to do with you without asking the Almighty.”

I remember now that I saw John Brown’s wife on her way to visit her husband in prison and to see the last of him. She seemed a strong, earnest woman, plain in manners and in speech.

This brings me to the period of the civil war. What can I say of it that has not already been said? Its cruel fangs fastened upon the very heart of Boston, and took from us our best and bravest. From many a stately mansion father or son went forth, followed by weeping, to be brought back for bitterer sorrow. The work of the women in providing comforts for the soldiers was unremitting. In organizing and conducting the great bazaars, which were held in furtherance of this object, many of these women found a new scope for their activities, and developed abilities hitherto unsuspected by themselves.

Even in gay Newport there were sad reverberations of the strife; and I shall never forget an afternoon on which I drove into town with my son, by this time a lad of fourteen, and found the main street lined with carriages, and the carriages filled with white-faced people, intent on I knew not what. Meeting a friend, I asked, “Why are these people here? What are they waiting for, and why do they look as they do?”

“They are waiting for the mail. Don’t you know that we have had a dreadful reverse?” Alas! this was the second battle of Bull Run. I have made some record of it in a poem entitled “The Flag,” which I dare mention here because Mr. Emerson, on hearing it, said to me, “I like the architecture of that poem.”

…………………………………………….

The journal further says: “Arriving in New York, Mr. Bancroft met us at the station, intent upon escorting Dr. Holmes, who was to be his guest. He was good enough to wait upon me also; carried my trunk, which was a small one, and lent me his carriage. He inquired about my poem, and informed me of its place in the order of exercises….

“At 8.15 drove to the Century Building, which was fast filling with well-dressed men and women. Was conducted to the reception room, where I waited with those who were to take part in the performances of the evening.”

I will add here that I saw, among others, N. P. Willis, already infirm in health, and looking like the ghost of his former self. There also was Dr. Francis Lieber, who said to me in a low voice: “Nur verwegen!” (Only be audacious.) “Presently a double line was formed to pass into the hall. Mr. Bancroft, Mr. Bryant, and I brought up the rear, Mr. Bryant giving me his arm. On the platform were three armchairs, which were taken by the two gentlemen and myself.”

The assemblage was indeed a notable one. The fashion of New York was well represented, but its foremost artists, publicists, and literary men were also present. Mr. Emerson had come on from Concord. Christopher Cranch united with other artists in presenting to the venerable poet a portfolio of original drawings, to which each had contributed some work of his own. I afterwards learned that T. Buchanan Read had arrived from Washington, having in his pocket his newly composed poem on “Sheridan’s Ride,” which he would gladly have read aloud had the committee found room for it on their programme. A letter was received from the elder R. H. Dana, in which he excused his absence on account of his seventy-seven years and consequent inability to travel. Dr. Holmes read his verses very effectively. Mr. Emerson spoke rather vaguely. For my part in the evening’s proceedings, I will once more quote from the diary:—

“Mr. Bryant, in his graceful reply to Mr. Bancroft’s address of congratulation, spoke of me as ‘she who has written the most stirring lyric of the war.’ After Mr. Emerson’s remarks my poem was announced. I stepped to the middle of the platform, and read it well, I think, as every one heard me, and the large room was crammed. The last two verses were applauded. George H. Boker, of Philadelphia, followed me, and Dr. Holmes followed him. This was, I suppose, the greatest public honor of my life. I record it here for my grandchildren.”

Fin